Life in Plastic: The Lush and Playful Upcycling of Günsu Hayriye Ozan

Photo taken by Mateo H. Casis.

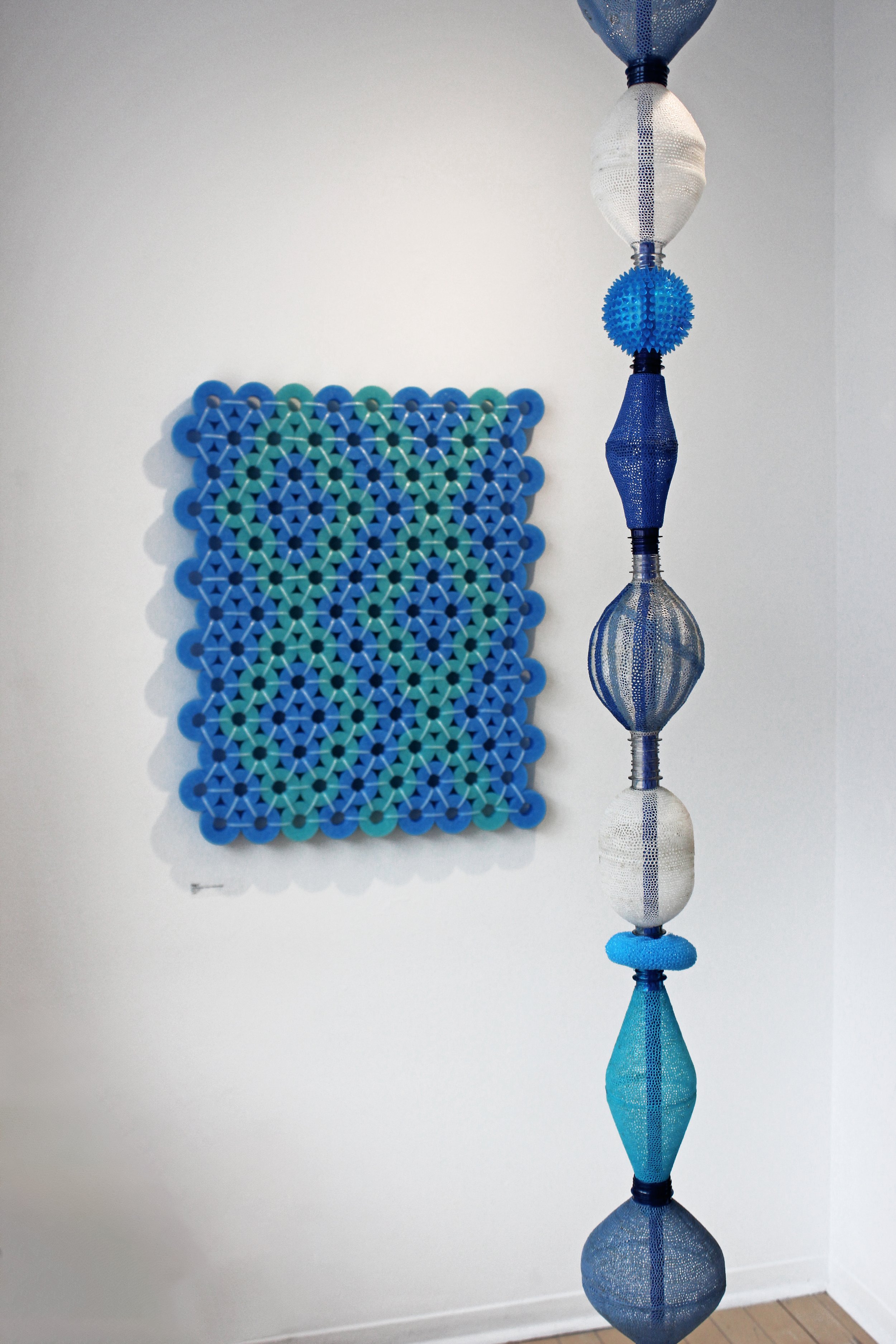

If you visited Nosy Mag’s third exhibition, Jinx! (June 9-17), you were likely struck by the bulbous blue Prayer Beads that hung gloriously in Wallack Gallery’s brightly lit entrance. An assemblage of shiny plastic tacks, bottles, and coils that have been carefully cut, burned, and melted into shape, this sculpture captivated our guests by its beauty and intricacy — despite the rudimentary nature of its basic element: discarded plastic.

As shocking as this work’s humble medium, is perhaps the fact that its author was relatively unknown to Nosy Mag’s team, and to many of our supporters. Günsu was born and raised in Turkey, where she studied fine arts, as well as graphic, textile, and fashion design. She has lived in Ottawa for five years. A relative newcomer to Ottawa’s ever-growing art scene, Günsu Hayriye Ozan has an exciting and rich practice that is sure to surprise time and time again. I had the pleasure of meeting her at her home studio for an interview, followed by a hot tea with turkish honey in her blissful backyard.

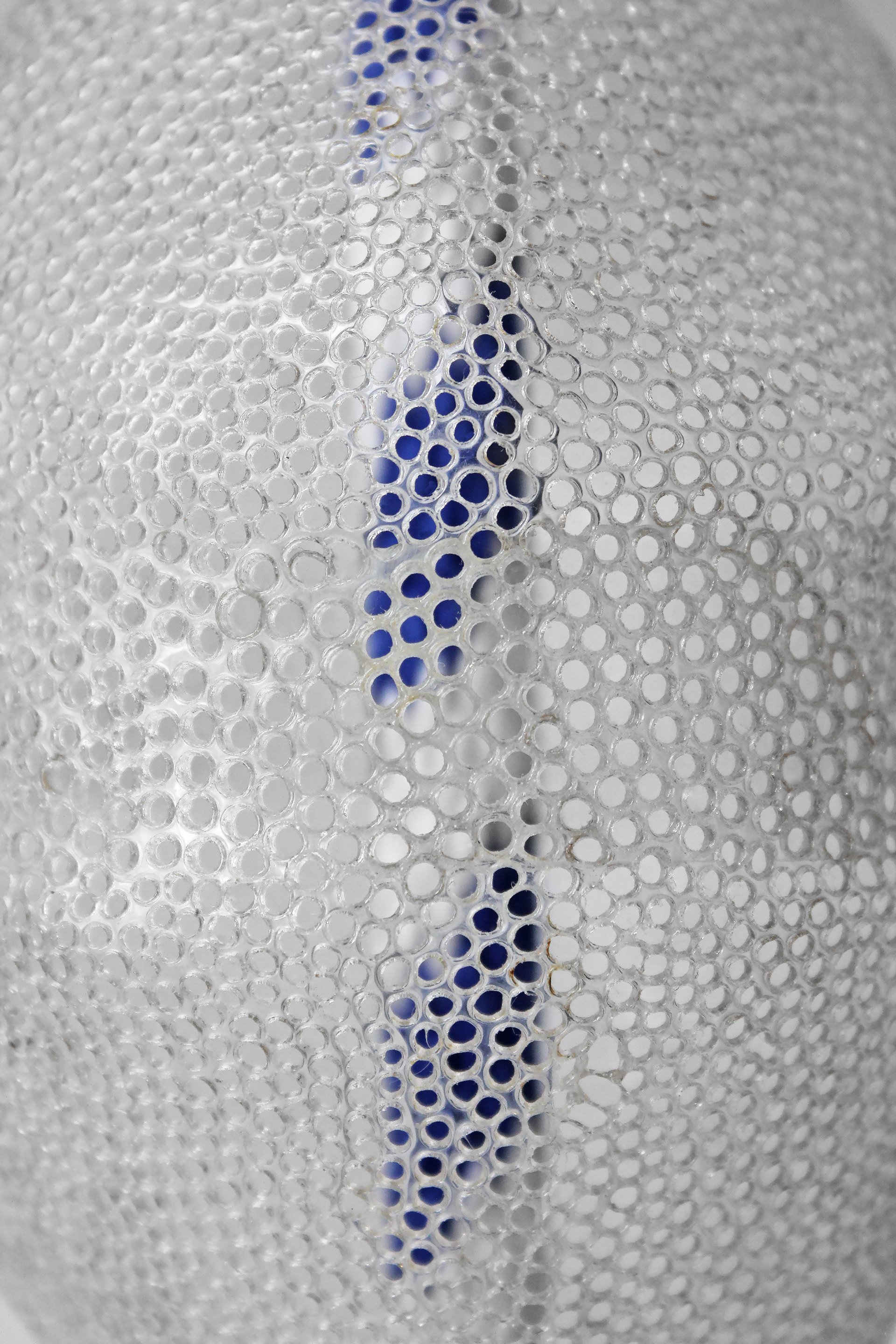

Günsu Hayriye Ozan, Prayer Beads (detail), 2023, upcycled plastic assemblage, 80 x 15 inches.

When I decided to interview Günsu, I knew very little about her practice, beyond what I had seen at Jinx! and at her recent show at the Ottawa School of Art. As I looked through her online portfolio, I was particularly curious about the path that led her to plastic. Indeed, her shift to the distinct style and medium we saw in Prayer Beads only occurred last winter: this work was the first project she undertook in plastic and was created in response to Nosy Mag’s call for submissions. “I’ve been a full-time artist for a year, and it all started with Nosy Mag,” she explained. Not to take undue credit or anything but I think we can pat ourselves on the back!

Upon arriving in Canada, Günsu completed the Fine Arts Diploma program at OSA, where she challenged herself to find the medium that “told her what to do” – something she had been yearning for since she began making art. She found this in plastic. The process of turning trash into art is far from glamorous: Günsu uses welding tools that she observed her father using growing up, x-acto knives, a heating gun, and a dandy home-made ribbon cutter made of a plank of wood with several blades on it that she uses to turn bottles into swirly plastic ribbons. Using these ad-hoc tools, she skillfully creates the illusion of fragility and preciousness by using a medium known for its disposability.

Günsu Hayriye Ozan, selection of works from the series Flowers, 2023, upcycled plastic assemblage.

MB: Your practice has really taken a turn since you started using plastic. Why do you think that is?

GHO: I was always looking for a medium that tells me what to do. I never liked painting or anything. I need a material that leads me, tells me what to do with it… Plastic has been giving me what I have been expecting from material because it reacts to whatever you do to it. I can heat it and change its shape or cut it, or put it in the dishwasher which will give it a weird shape. And the material is very limited: I only have a few colours, like blue or green or clear. I like being limited by my materials. If I have too many choices, like paint that can turn into infinite shades and colours, it gives me anxiety. And since I’m so into blue, I look for blue constantly in plastic materials like pool noodles, straws, zip ties and sponges. Also, plastic is so accessible. I used to work with ceramics, but its demands in terms of space, tools, and dedication have led me to reconsider. While I appreciate the idea of a dedicated studio for ceramics, I find that my creative process should unfold naturally without excessive pressure. The comfort of creating at home is essential for me, and pushing too hard feels counterproductive.

Günsu Hayriye Ozan, Nebula, 2021, mixed media on paper, 66 x 34in.

Günsu Hayriye Ozan, Shake the Dust off Your Feet, 2021, Porcelain, 6 x 9 x 10 inches.

MB: Ceramics and painting are also very expensive.

GHO: Yes! And I want to feel comfortable experimenting with the material I use. If I pay a lot for a material, I feel stuck with the idea of using it well – like I have to make something really good with it. I don’t want to hear that voice in my head. I think it would be the same if I were rich; I just don’t want to waste! And I really don’t want to worry when I’m making art. I want to feel just like a kid —they don’t care if something is cheap or expensive, they just play with it. Plastic is everywhere, everything that we buy comes with a plastic packaging. And if I start messing around, even if it doesn’t go well, I have a substitute right there. I don’t have to worry. When you start making something with that attitude, it always leads you to something good because you’re not reflecting worry onto whatever you’re making. It’s really like meditation. You don’t get to decide what to do next, it’s already decided. When you heat plastic, it creates a new shape.

Left to right: Günsu Hayriye Ozan, Miss Clear Push Pin, 2022; Deep Diving Jellyfish, 2022; Prayer Beads (detail), 2023.

MB: You mentioned wanting to revert back to being a kid, just playing with materials, without the burden of expectations. I know you teach courses to kids at the Ottawa School of Art. I saw some of the works in your classroom when I was taking a painting class. They were funny, fresh, and weird! Does that play into your practice?

GHO: I was trying to teach the kids to get to know the material first. I was also trying to remember that they are kids — don’t be harsh on them. Let them play, let them figure out what they want to do and go for it - individually! They’re always coming up with really interesting ideas. That’s why I love teaching, they’re part of my process!

MB: I like this idea of letting go and letting the medium guide you. By playing with plastic and letting its prefabricated, industrial shape guide your hand, you allow beautiful shapes and textures to emerge. But if I picked up a water bottle, it wouldn’t speak to me in the same way that it speaks to you. Why do you think you’re so receptive to this material?

GHO: I actually have three different upcycling artists that I’ve been inspired by, and each has a different approach to plastics. What makes the medium so rich to me is that you can see how an artist’s brain works when you look at their works. Despite sharing materials and processes, the inherent uniqueness of our life journeys contributes to completely individual outcomes.

Left to right: Günsu Hayriye Ozan, Prayer Beads, 2023 (detail); Plastic Bottle Pole, 2022, Mixed Media (upcycled plastic, glass beads, metal), 40 x 17 inches; Blossoms | Gathered, 2023, upcycled plastic assemblage, 23 x 62.5 inches, at Playthings, Lee Matasi Gallery, August 2023.

M: Other than plastic artists, who inspires you?

GHO: Ruth Asawa. She had six kids and yet she made her way. She created her own world. And Yayoi Kusama. Both of them have one thing that they’re obsessed with, and the material gives you so many chances to make something. In terms of the shape you can create out of that technique or the size, the scale that you work, you can make a repetitive pattern, and it will give you something. They have a basic shape or technique, and through repetition they can create something totally different. That’s what makes me really excited about their work. Like Yayoi Kusama and circles: some are heavy, some are small, some are infinite, shiny, matte… it’s endless. Combinations are endless but you only have one thing. Ruth Asawa works with wire; she makes so many things just with that technique. Some people might find it really boring but even the idea of having a different direction in the next work is so exciting.

MB: Speaking of building on your medium, we’ve Seen Prayer Beads and your beautiful exhibition at OSA, where giant pool noodle flowers sprung from the ground. It felt like I was in a video game or alternate universe! Do you know what you’ll be working on next?

GHO: I have two projects I’m working on, both building on Prayer Beads. I’m aiming for a continuous evolution in my work, as I add new elements every time I showcase them. For instance, my upcoming show (Günsu performed with Eylül Bozok at Debaser’s Pique winter edition on December 9th at Arts Court) will present my existing works and incorporate a contemporary dance performance, examining the creative process. The idea initially involved displaying my artworks only, but I wanted to avoid monotony. So, we decided to recreate my studio in the performance space, creating art simultaneously with the dance. The performance aims to showcase the evolving nature of my ideas, with a dancer interpreting the voices in my head –shaped by people and life experiences past, present, and future. The interactive aspect allows the audience to influence the performance, mirroring how they shape my ideas and impact my creative process.

Günsu Hayriye Ozan and Eylul Bozok, Menu of the Day, 2023, Performance/Mixed Media Installation at Ottawa Arts Court, as part of Debaser’s Pique. Photo: Curtis Perry.

The interactive aspect allows the audience to influence the performance, mirroring how they shape my ideas and impact my creative process.

I am also working on a project on a large canvas. I’ve been weaving strings of plastic, which I enjoy so much.

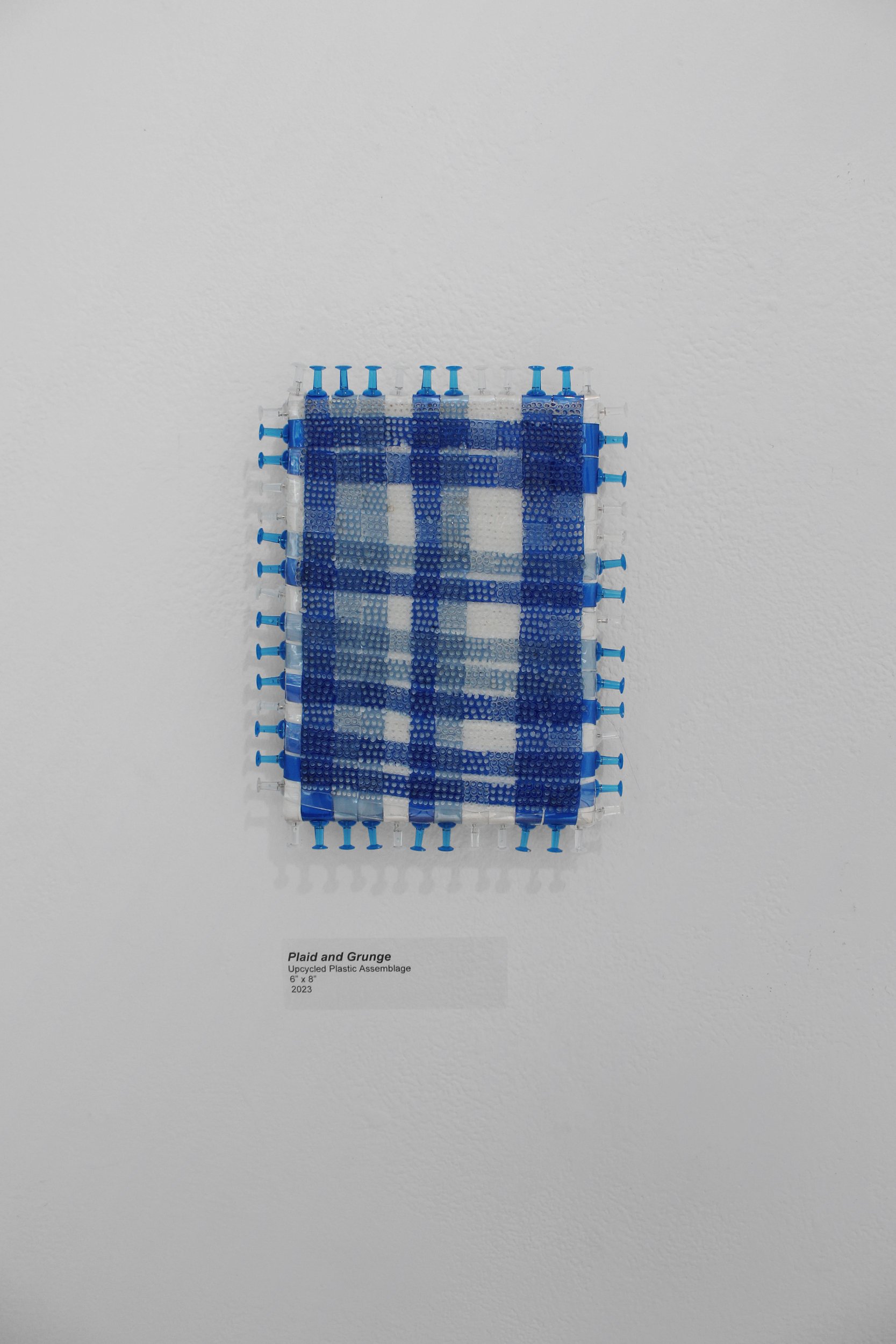

Günsu showed me several small canvases covered with latticed plastic ribbons, sometimes uniform in colour, and sometimes alternating to produce new patterns.

Günsu Hayriye Ozan and Eylul Bozok, Menu of the Day, 2023, Performance/Mixed Media Installation at Ottawa Arts Court, as part of Debaser’s Pique. Photo: Curtis Perry.

MB: How are you finding the process of creating sculptural works that are flat, and that follow patterns?

GHO: It’s my least favourite because it has borders. Because it has patterns, I have to follow a rule.

MB: So there’s no margin for error?

GHO: Yeah! So I probably won’t repeat this again. But like I said, I don’t regret it because I still have the ability to make new material. It doesn’t hurt me. I didn’t lose anything by making it.

Left background: Günsu Hayriye Ozan, Rug 1, 2023, Polyethylene foam assemblage, 28 x 34 inches. In Playthings, Lee Matasi Gallery.

Left foreground: Günsu Hayriye Ozan, Havya, 2023, upcycled plastic assemblage, 6 x 77 inches. In Playthings, Lee Matasi Gallery.

Right: Plaid and Grunge, 2023, upcycled plastic weaving, 6 x 8 inches.

MB: I like this one (Plaid and Grunge), it reminds me of a picnic table

GHO: This is also a childhood memory! I used to steal my dad’s plaid shirts, and I was really into grunge, into Nirvana.

MB: It seems like much of your work hints at storytelling, both personal and broader – cultural. What do you hope to convey with these works?

GHO: When I started, I was making simple things like flowers. But I asked myself, What’s the purpose? Am I going to put them in a vase? On the wall? That’s boring. Prayer Beads is my attempt to make those flowers make sense. Lately I’ve been reflecting on my childhood memories, my family and the land where I grew up. When I was initially making plastic works, they didn’t make a lot of sense to me. But when you step away from what you’ve done, then it starts to speak to you. I got the idea for Prayer Beads because at the time I was longing for home and feeling a bit depressed while I waited for my work permit, and I was looking for something that makes me feel comfortable. I thought, what from my childhood would I enjoy doing the most? When you grow up, you stop enjoying small things and you seek bigger things, satisfying things that are more money related. So I thought, when I was a child, what little things did I like to do? I remembered picking flowers and playing with my grandmother’s bead box. She kept a box of beads she used to make prayer beads, that protect you from bad souls. My grandmother used to pray over beads that she made and she would give them to people who just bought a car to protect them. As a child I just wanted to play with them. I realized, since my grandmother passed away, that making my own beads helps me feel less stressed.

Günsu Hayriye Ozan, Prayer Beads (detail), 2023, upcycled plastic assemblage, 80 x 15 inches.

MB: Every bead is so intricate, and they’re all different. Why is that?

GHO: Despite my appreciation for minimalism, my artistic approach is maximalist. My brain naturally tends towards detailed and elaborate concepts. So the philosophy behind the unique beads is how people are so one of a kind, each of them, and you feel a different way when you interact with them or you’re around them. Just like each person has their own style, their own way of speaking, so many variables — that’s my source. I think you can interpret the beads as human.

MB: Why blue?

GHO: Blue comes from the evil eye, and beads that are blue protect you from that eye. I think the blue comes from there. I get to decide!

MB: It sounds like the meaning of your works is deeply personal, and still evolving.

GHO: I’m trying to find a deeper meaning every time I make something, but really, it’s so basic. I make these to cheer myself up. The driving force behind my work is really the desire to bring the ideas that have accumulated in my mind to life, providing a sense of relief through expression. It’s a form of self-care because it's a natural process for me. It doesn't feel obligatory; rather, it's similar to a printer, my hands translating ideas into tangible creations for communication. Art is my most effective means of communicating with people.

MB: What do you hope viewers of your work take away?

GHO: I don’t know if someone would be able to tell what my art means in a way that I want it to be understood. But as a viewer, I just want to understand the artist. I want to know who the artist is, how they use the materials, how they know each material is suitable for their practice. I’m mostly interested in that part. Once you know that, it all starts to make sense. That’s what happened with Guillermo Trejo and Marisa Gallemit (Günsu had told me, in a previous conversation, how much she learned from listening to these artists talk about their work). They insist on using a particular material, and you don’t know why until they reveal something about themselves, and all of a sudden it all makes sense.

I’m so grateful that Günsu was so generous with me as she walked me through her process! Thank you, Günsu, for letting me snoop – both in the drawers of your studio and your mind! (too much?)

You can find Günsu on Instagram (@gubtus) and at www.gubtus.com, and around the city.