Creating Space: A Conversation with Nosy co-founder Atticus Gordon

Credit: Atticus Gordon, Ai Veneration Monument. Oil on birch, with zinc chain and found objects. 97’’x18’’x18’’ 2022

The genesis of an Atticus Gordon painting often appears as a sketch or picture in Photoshop. He says his most successful pieces start with “a mix between [a] plan and [an] improvisation.”

As he brings the work to a larger three-dimensional space, he chases an emotional flavour that he found difficult to describe.

“You can look at two paintings and one really speaks for whatever reason and one doesn’t, even if they’re the same subject matter. It’s a hard thing to quantify, but that’s what I’m after.”

As one of Nosy Mag’s co-founders, Atticus identifies himself as a “firm believer in space and creating space.” When the magazine kicked off two years ago, part of his vision was to help foster a vibrant arts community in the city, teeming with resources, collaborators, and new opportunities.

“[Space] accounts for so many things, like where you work, where you exhibit your work, where people gather, where people buy work,” he said. “It often revolves around that physical entity.”

Atticus chatted with me from the white interior of his Chicago studio over a Tuesday afternoon Zoom call. We spoke about art scenes moulding to the environments that contain them, the importance of artists’ presence in a space, and how locating oneself within a creative community can change the trajectory of their craft.

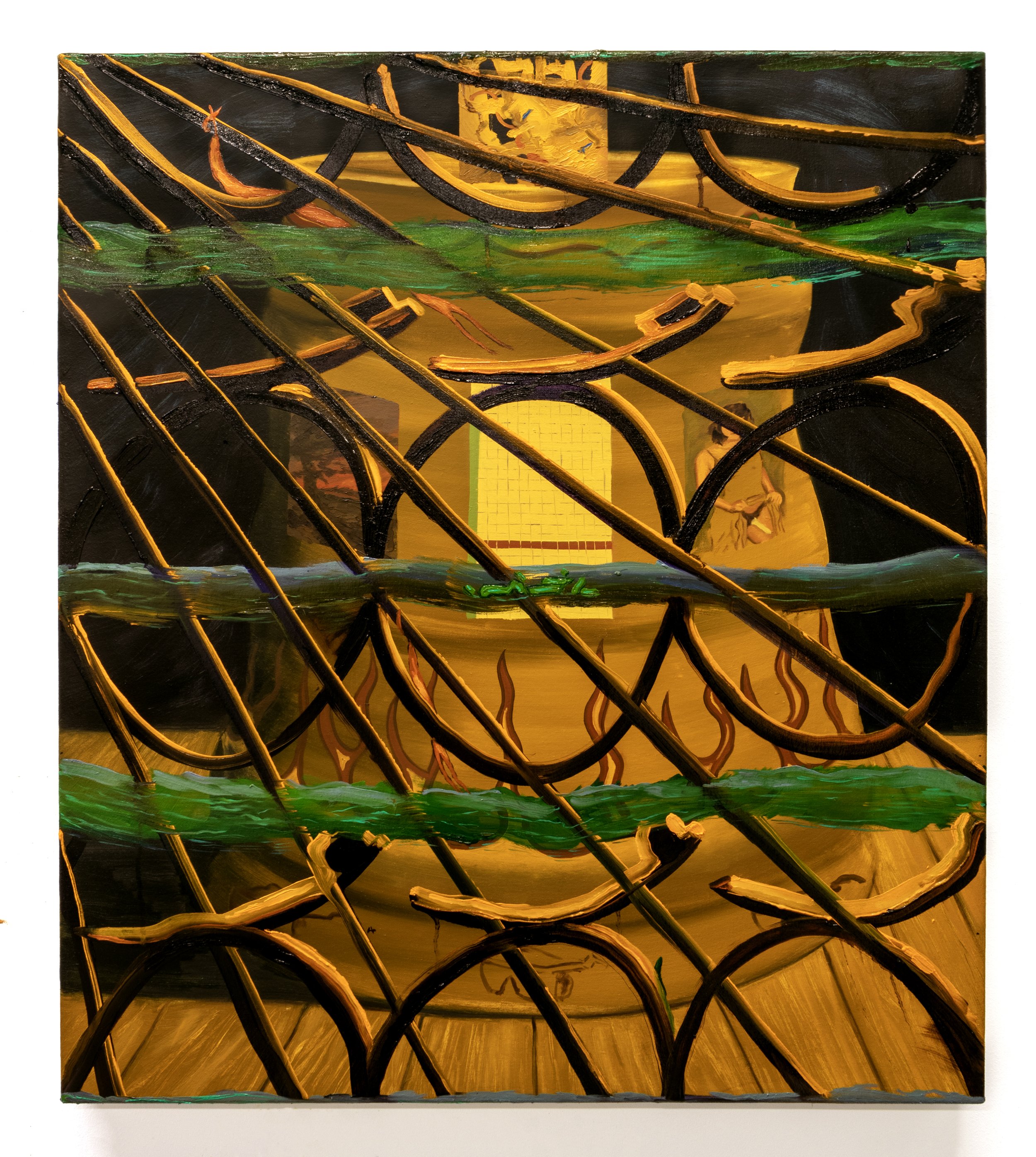

Credit: Atticus Gordon, Untitled (Hierarchy Painting)_O/C. 84’’ x 72’’ 2023.

Atticus is a painter and installation artist hailing from Ottawa, with stints in Montreal and Berlin. These days, his practice is set up at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, but he maintains a “firm footprint” in Ottawa through his gallery and relationships.

“Chicago is a fantastic art city,” he expressed. “There’s no shortage of artist-run spaces, like DIY stuff all the way up to major galleries, museums, and people practicing and working here.”

His practice intersects sculptural installation work with flat painting. He brings components of contemporary painting on stretched canvas or panel to three-dimensional space using different materials, oftentimes wood. Using a collage basis, his works often overlay fragmented representations of people and places to reinvent new scenes.

Credit: Atticus Gordon, Untitled (cosmology painting)_O/C, 48’’x60’’ 2023.

Atticus tends to avoid specific stylistic descriptors of his work, though many people contextualize it in surrealist terms. To him, the most important qualifier is the work’s emotional resonance. “I’m mostly interested in the medium of painting, what it does, what it has done, and how I can experiment and play with that to create something that I essentially find exciting,” he expressed. “If I’m getting surprised by it, it’s something I haven’t seen before[and] that’s sort of what I strive for.”

“Painting, or any art, can become something that reaches out and has a life force or an energy of its own.”

Like many successful artists, the complexities of his practice did not unfold in a vacuum. Starting as early as childhood, his artistic journey is grounded by the impact of creative mentors, peers and spaces.

Credit: Atticus Gordon, Obscured Data Container, 30x36” oil on canvas, 2023.

Atticus initially discovered his curiosity for building models as a child attending Waldorf education, a form of elementary schooling modeled after the philosophy of Rudolf Steiner. At these schools, emphasis is drawn away from traditional grading schemes and toward creative and tactile skills like gardening, painting and building. “Certainly an origin point of my interest in building things, painting and sculpture comes from that,” he recalled, after pacing around to reactivate his studio’s automatic light sensor. He then stated a “very big moment” in his journey was getting into Canterbury, a local arts high school, for visual arts. “I think my life could have gone in a very different direction had I gone to a different high school.”

At Canterbury he became interested in painting and looked to many experienced art teachers while he honed the skill. He brought up one in particular, Tim DesClouds, who had a “major influence” on his interest in combining elements of sculpture and painting. As a post-secondary student, he initially attended UOttawa for sociology, but quickly switched into visual art. He said while the program exposed him to a wide scope of mediums like drawing, video and film, he left with a “prolonged interest” in sculpture and painting.

Feeling lost is a risk you’re likely to incur as an artist. For him, leaving a fine art undergrad and entering the world as an emerging professional artist was jarring.

“It’s always a pretty hard time when you finish an art degree because you were at a place where you have community, you talk about your work, you have space to make the work – it’s part of your routine. And then that’s just suddenly gone and you’re like, what the hell am I going to do? I have to make ends meet, but I want to keep making art,” he shared.

Atticus said moving in with his parents after his undergrad was a challenging sacrifice he made for his art’s sake. It allowed him to fund studio space, find time to paint and eventually embark on a four-month residency at a commercial gallery in Montreal. Regarding the onset of the pandemic, he described the sudden influx of free time to spend in the studio as a “major momentum push” in honing his craft and dialing into his unique style. Shortly thereafter, Atticus attended a 2020 residency at SomoS in Berlin, where creative production is heavily marked by its history as an artist hub after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Today, his journey finds him pursuing his master’s degree in Chicago. He said it is challenging being an outsider, as he finds his place in a totally new arts community after establishing himself in Ottawa. However, he managed to find collaborators and exhibitions in Chicago by sustaining the trajectory of the practice he built in Ottawa.

For emerging artists, he said, a major benefit to forming an artistic practice within an educational context is the relationships you build with other artists, both personal and professional. The side effects are more confidence in what you can do, collaborative opportunities and broader knowledge of your craft. “It essentially allows you to not reinvent the wheel. You’re in a spot where people have already done what you want to do and you can learn from their example.”

Credit: Atticus Gordon, Networked Sublime, 97x60” oil on canvas, 2023.

Reflecting on the spaces he occupied throughout his career, Atticus found that the economic, bureaucratic and social atmosphere of a community can shape the artists within it. For example, he noted the artistic landscape in the US has less public funding than Canada’s, generating more opportunities in the commercial and DIY arenas. “Right away, that’s going to change what kind of work artists are making in the community,” he explained.

In Berlin as well, the 1990s brought in a tide of artists taking advantage of the surge in affordable housing and studio spaces. He said the robust art scene there still reflects how communities react to economic possibility.

When folks ask what is needed for a thriving art community in Ottawa, his answer is simple: “people need to not leave.”During his time here, he saw a scarcity of exhibition spaces, affordable studios and commercial opportunities driving artists away. “I think it’s a lack of resources,” he explained. “It’s just more difficult to support yourself, commercially or not.”He said a lot of his exhibition work in Ottawa, including curation projects at Wallack’s on Bank Street, focuses on “[building] a spot where people can meet and talk about art,” which will hopefully encourage more funding and exhibition opportunities in the city.

DIY initiatives like Nosy Mag are part of that solution, by platforming local artists, facilitating commercial opportunities, and hosting community-building events. He also noted that they empower artists outside the institutional domain to hear about funding opportunities that normally only circulate within traditional or educational circles.

Ultimately, a major dimension influencing art communities is the artists themselves. Atticus said finding long-term collaborators to create, and build exhibitions with, was paramount to his own success as an artist. “It’s hard to qualify what that is, but you need friends to look at the work, get excited about it, give you advice about it, and also gallerists and people to support and show and believe in the work,” he said.

“It’s a whole network of connection and friendship.”