In the Closet and Against the Fridge: Sitting Down with Sam Loewen

Bolduc, Pat, Sam Loewen Headshot. Courtesy of the artist

Sam Loewen produces thoughtful and provocative works primarily exploring his identity and experiences as a queer man. I recently had the pleasure of meeting him for a drink and interview, during which he shared insights on his complex history, process, and intentions.

After avidly scrolling through Loewen’s website and socials, I was beyond excited, if not a little nervous, to get to know this smart, inquisitive, sensitive, quietly funny and subversive artist. I sipped on my beer and anxiously awaited his arrival so I could dig into his work: a pastel-coloured, aestheticized array of screen-printed images and objects that, upon close examination, feature highly suggestive images of male bodies and references to casual sex, bondage, online dating, queer intimacy, and millennial online culture.

We met at Irene’s Pub across the street from Studio Sixty Six where Loewen has worked as Art Director for the past three years. We started exchanging pleasantries and brief intros, during which I learned, much to my surprise, about Loewen’s upbringing in Southern Alberta and training as a Christian missionary for the Baptist Church. I asked myself, as you likely are too, how does one go from a conservative Christian upbringing to making art with pornographic homoerotic imagery in the span of ten years? Loewen’s private life is his own, so I chose not to pry, but what I gathered is that he was raised with a sense of respect, care, and compassion that he has carried into his professional and personal life, despite the major shift in core values and attitudes he evidently developed due to his identity, desires, and personality.

Sam Loewen: I was raised Baptist and studied as a missionary. I did biblical training in Hawai’i and was sent to Rwanda for four months. I was aware of my whiteness and how it affected my relationship with locals, so instead of doing regular missionary work, I taught photography. No preaching! In a lot of my work, I look for an answer to the question: “where does Christian ideology meet my queer identity?”

Loewen was still closeted during his Bachelor of Fine Arts in his hometown of Lethbridge in Southern Alberta. During this time, he was fascinated with the gendered dynamics of colour. Creating a sort of double life, he explored his sexual identity by using gendered and romanticized paint colour names as the starting point for conceptual artworks, allowing him to meditate on his identity while concealing his queerness from his family.

Loewen, Sam, Country Queers (Light Blue), 2019, Over-dyed screen-print on handkerchiefs. Modified edition of 20. Courtesy of the artist.

SL: I’m colour blind, so I see colour, but it’s distorted compared to how others see it. My sister used to write the names of colours on my pencils. I became very familiar with names of colours and during undergrad, before I came out, I noticed that the colours of latex house paints are very gendered. I used these to generate concepts for paintings and reference a type of queerness that was meaningful to me but revealed nothing to my family. This coded communication is very common in the queer community: this goes back to hagging and cruising and other ways in which queer men have communicated desire historically.

During his Master of Fine Arts (MFA) at the University of Ottawa (2018), Loewen, who had since come out, made his work explicit in more ways than one. His queer sexuality, and desire for both sexual and non-sexual intimacy, were put on display in a most erotic and beautiful fashion.

Loewen, Sam, The Catch I, 2019, Screen-print on paper mounted to panel. Edition of 3. Courtesy of the artist.

After his MFA, Loewen worked as a graphic designer for a few years, has taught Business of Art courses at the Ottawa School of Art, and has continued his own art practice in his personal time while working at Studio Sixty Six. When he’s not at work, he removes his art director, curator, and social media hats, turns off his email notifications, and becomes an artist, home cook, friend, and parent to two-year-old puppy Bosley. Given that he no longer has the time, space, money, and tools that he had as a full-time student, Loewen’s output has understandably changed. Rather than using the technologies available to uOttawa art students, he now uses a Cricut scrapbooking machine to print most of his work, which is more digital and small-scale than ever. He also views his work less in terms of productivity and more as a part of his daily life. He describes his work as “relationally driven:” it has become “about time spent and how activities are done. A drawing doesn’t have to be a drawing; it can be a folded shirt. It’s about participating in an activity, even if it’s domestic: it’s often folding, mending, and cooking.” In fact, the space he uses now is a (hopefully large) closet near his kitchen, an inconvenient but ironic twist given his history.

SL: As a queer artist I kind of love it. I have to go back into the closet to do my work. There’s a lack of space, but it works with the intimacy I seek out: I love that I’ll be working and cooking a lavish meal at the same time. It’s about intention and self care and [sigh] buzzwords, [he embarrassedly giggles.]

Loewen, Sam, Closet Studio, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

We started off discussing Loewen’s relationship to theory. Having completed an MFA, his work is extremely well-researched and combines aesthetic practices with a robust theoretical understanding of contemporary queer theory, poststructuralist theory, and relational aesthetics. He cites Sara Ahmed as one of his principal references. He loves the typographic and conceptual art of Lawrence Weiner and Gary Neil Kennedy, and “of course,” the graphic, conceptual, queer art of General Idea.

MB: Tell me about your logo, the nail polish emoji. It seems to echo the contemporary queer symbolism I often see on social media.

SL: I’m really interested in semiotics! I’ve used the nails emoji since undergrad. To me, it’s like a millennial hieroglyph.

MB: I never would have assumed that this fun emoji was a choice related to semiotics! How do semiotics and other theories fit into your current practice?

SL: For me, theory primarily has a research function. I get really excited by ideas, most significantly those of post-structuralism: relational aesthetics, queer theory, etc. I’m always thinking, “why this material?” I’m a printmaker, but not really; I typically work in whatever the medium needs to be for the concept. I create images that resonate for me first.

Loewen, Sam, Installation View: MFA Thesis Exhibition Reliqueery, 2018, AxeNeo7, August 2018. Photo Credit: Julia Martin.

A work I was particularly excited to discuss with Loewen was his thesis show, Reliqueery, at AXENÉO7. One of many plays on words in Loewen’s practice, this term combines two major and at times contentious influences in his work: his Baptist upbringing and his identity as a queer man. In Reliqueery he arranges works that exhibit his interest in queer love, intimacy, and sexuality as relics of Saints might be displayed for pious churchgoers. Elevating evidence of his queerness to the status of holy objects, Loewen subverts harmful narratives that associate queerness and shame, presenting instead a thoughtful collection of images and objects that hold space for contemplation and for the exaltation of queer icons.

As part of Reliqueery, Loewen included a performance, Lavons, during which he cleaned participants’ hands using lavender-scented soap he made with his mother and anointed them with lavender oil. Two references in Canadian art immediately came to mind when I watched the video of Lavons. First, I thought of Devora Neumark and Tali Goodfriend’s And how shall our hands meet? Performed in Montréal in 2006, this artist intervention took place during a protest in solidarity with Lebanon against Israeli invasion. By bathing each-other’s hands in olive oil, the artists use cleansing and touch as a healing gesture. Likewise, since I had just visited the General Idea retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada, I thought of the politics of hygiene and contamination that have been imposed on queer people, particularly queer men during the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Although we now know that HIV cannot be transmitted by touch, I know that there has been and likely continues to be stigma surrounding touch for HIV-positive people.

Loewen, Sam, Lavons II, 2018, Installation and participatory performance, AxeNeo7, August 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

MB: I can’t help but wonder if these were references you had in mind when constructing your own work of cleansing hands. Did you intend for this work to be a political gesture?

SL: I’m not familiar with that first reference, but I see how it’s similar! Sara Ahmed’s writing on trans experiences and queer theory affected my thinking on this work. She discusses the need for evidence when telling your story. She relates this to Christianity and the story of Doubting Thomas: Thomas wants proof of the “holes” or “scars” of Christ [before he can believe he was crucified and resuscitated.] Being asked to show their “holes” or “scars” to be believed is something trans people often experience from incredulous strangers who mistrust their gender presentation. At the time, my friend was transitioning and underwent gender confirmation surgery in Toronto, and I was his caregiver. His chosen name, Sebastian, seemed extremely loaded: Sebastian was a Catholic saint who has been co-opted by the queers since the HIV/AIDS epidemic because he is saint of brotherly love, athletics, and victims of the plague. With HIV/AIDS, which was a plague, AIDS-riddled bodies were emaciated and unable to maintain athleticism, and brotherly love was vital among queer men. The queer intimacy and non-sexual relationship that emerged in my relationship with Sebastian inspired this work. I explore closeness as an umbrella for my practice. Having to bathe Sebastian encapsulated what this meant, so I re-created this cleansing practice in the gallery. I washed participants’ hands, allowing for nonsexual intimacy; just closeness and touch and care. The results were amazing and unexpected. I created an olfactory experience as well, with the soap that was scented with lavender from my mother’s garden. I wanted it to feel special and calming. I massaged participants’ hands and asked them about any evidence of their lives that might be present on their hands, like rings or scars, and I listened to their stories. I was so taken with how open people were with it. It was vulnerable in both ways. One fella came because he had been told he was HIV positive and didn’t know who else to tell. Another woman, with terminal cancer, just wanted to be touched. After the massage, I anointed the participants’ hands with lavender oil and gave them any extra pieces of soap that were left over from the session. I’m now thinking about how this is relevant during COVID. People started reaching out to me about how they were using their soap, especially nurses after a long shift. The soap from years ago was finally used as a gift to themselves; one of care and relaxation. It was a precious object used after gruelling shifts.

MB: Let’s talk about your other works: prints and objects. I want to ask you about your use of material. You use printing processes on multiple sexually charged materials like bedsheets, hankies, pillows, and rope. How does their practical use interact with their social and artistic functions?

SL: I think this mostly comes from my love of kitsch, its blend of high and low. I love to combine a humble material with something very luxurious. The queer community does alchemy through kitsch and material: we can get cheap things from the thrift store, with very little funds, and make something fabulous. We can live in the fantasy of being opulent and luxurious. We see this in drag, and I bring it into my work. I also just have a real love of raw material.

Loewen, Sam, Plush Bois, 2020, Screen-print on bedsheet, quilted and mounted to wooden panel. Edition of 2. Courtesy of the artist.

MB: Although there is undeniable subjectivity in your work, there are rarely faces, names, or identifiable features. We find body fragments, backs of heads, repetition, and general terms like “boyfriend,” “bois,” and “country queers” that suggest vague, perhaps even interchangeable identities, like in Clone. We often find this idea of the double in queer theory: the mirror self, the person you wear as a mask or shield. I can’t help but wonder if the men represented are or could be you or your double, hidden by layers of mechanical process. Would you say you’re exploring your own image? Is anonymity important in your work?

SL: It’s a little bit of everything. When my work has the back of a head or a silhouette or a torso, it represents the anonymous profiles of men on [dating/hookup] apps. Like an anonymous desired person, a ghost, someone out of reach, an unwilling participant. Sometimes it is my own body and it’s cropped as a reference to this very weird hookup culture. Some other crops legitimately just come from porn. I’ll see a random clip on Pornhub and think, “that’s a beautiful still,” or “that’s a beautiful pose”— And the person is being fucked against a fridge. In terms of repetition, I find I can strengthen the symbols I want to convey through multiples, like ropes or multiple prints.

Loewen, Sam, Detail: Clone, 2019, Screen-print on paper mounted to wood panel with hand spun bedsheet rope. Variable edition of 6. Courtesy of the artist.

Loewen, Sam, Rope Study No. 1, 2018, Screen-print on paper. Edition of 4. Courtesy of the artist.

MB: Another “reference” is your advertorial-like style. You have an extremely polished, prim aesthetic that borders on design – which makes sense given your graphic design background. Relative to process, the reference to pop art is inevitable.

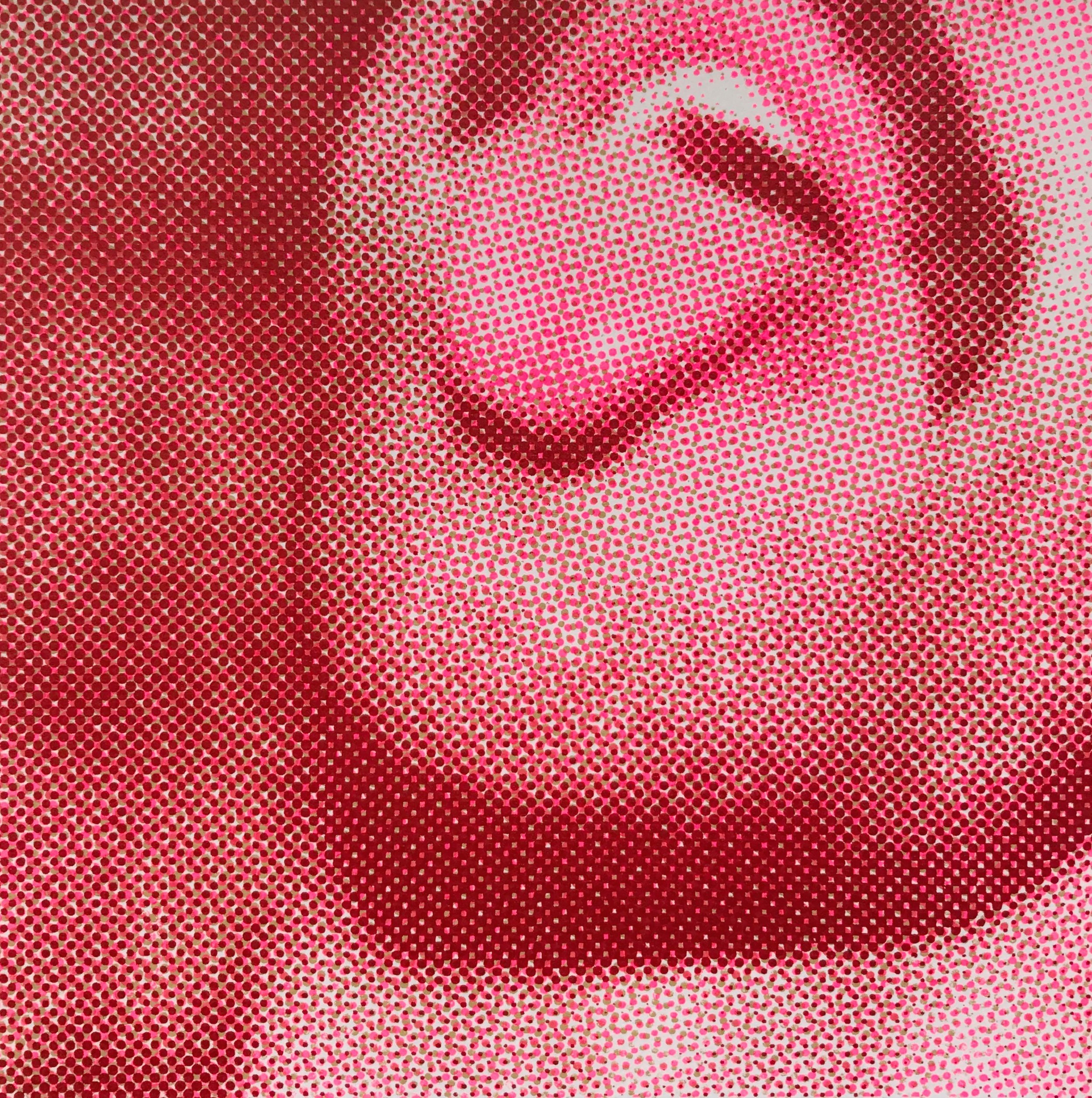

SL: I have a background in design, and I love geometry and hard-edged shapes. I don’t see art and design as separate. I’m the grey space. I use a lot of processes that recall vintage advertising. My half-toned dots harken back to vintage gay porn because that’s how printing was done. Obviously, there’s also reference to Warhol and Haring – the gay forefathers! I also want to acknowledge that race is present, so my use of colour is important: it’s so that others may identify. This is why I use lots of cropped images and non-natural colours: these images aren’t universal to all, but they are also universal to the queer masculine community.

MB: The half-toned dots also create a further layer of fragmentation to your images, as if the men were seen through a gauzy or punctured screen or a sieve. Historically stigmatized, fetishized, and pathologized bodies are put on display but partially hidden. Can you speak to your intention here, and how this impacts the viewer’s gaze?

SL: In my experience of queer romantic spaces, particularly app culture, romance is mediated through a screen.

MB: Do you hope that your work turns people on?

SL: I know some people have sought out my pieces for their bedroom because it inspires an erotic response [he giggles]. In my work as well as in curation, I like to question “how does the body feel?” I like when I can make my work make someone’s body move. I often ask myself: “How do I give my work agency?” I adore Janine Antoni, and she has an intimate relationship with her work in the studio. There’s a clip of hers I love where she asks, “what is my work capable of? When will our relationship end?” Likewise, I’m not making a surface; I’m making an object. And it will have a relationship with other people.

MB: The relationship between your work and other people must vary a lot depending on how familiar they are both with art history and queer pop culture. Your work is full of references, many of which I probably didn’t catch since I’m not queer, or a man, or Christian, or a millennial. I am an Internet addict and single person who attempts to date online, though, so it was hard to miss the references to meme culture, online dating, and hook-up culture, especially in your titles. What’s the intention there? Would you say you’re speaking in code to people who know that language, or are you intentionally confusing people who don’t?

SL: That’s exactly the goal! Not everyone is going to be in on it, and that’s what makes it safe. Not everyone’s going to get the work and that’s ok; it means it wasn’t for them. I don’t assume that my audience is dumb. Some things are meant to be left unsaid.

Loewen, Sam, Read 3:33 AM Looking 4:11 AM, 2019, Screen-prints on stretched bed sheets. Edition of 1. Courtesy of the artist.

Talking to Loewen only exacerbated how much I appreciate and am grateful for his work. His research into materials, subject matter, and emotion make it beautifully well-rounded. He mentions that not everyone is meant to understand his references but that he hopes all feel safe in his work’s presence, which I find a humble approach to making work that is both personal and effective. As a straight, younger, and evidently less sexually transparent person than Loewen, I still found a sense of peace and solace in his works. As much as they are exotic to me, I felt overwhelmed by a much-needed sense of acceptance, intimacy, and openness that they allowed me to experience.

You can find Sam Loewen’s work on his website and Instagram. Recently, his work was included at SAW Gallery’s SAW Prize for New Works exhibition. He will be part of a group show at Karsh-Masson Gallery opening in January 2023.